In Search of the Geisha

I was in a budget barbershop in Ottawa when the gregarious Englishwoman cutting my hair asked about my post graduation plans. After telling her that I was soon leaving for Japan, she glibly replied, “Going to get your geisha?”

I made a non-committal response. Even though I was sure that she didn’t literally mean that I was going to look for a woman of uncertain virtue, the likely alternative--a demure Japanese girlfriend--was not a motivating factor for my decision to spend a year overseas.

Upon arriving in Japan, I read a series of books that challenged my preconceptions about geisha. One of my first purchases was the Gluck family’s exhaustive (and self-referential) guidebook, Japan Inside Out, which focused on the geisha’s role as an “arts lady,” dedicated to keeping a party moving with song, dance, music, and the pouring of sake.

I subsequently read two Japanese novels in succession that added ambiguity to the Gluck description of the role of geisha. The first was Botchan, a comic novel by early twentieth century author, Natsume Soseki. In one scene, a group of teachers from the protagonist’s school attend a banquet hosted by geisha. The action unfolded in a manner I recognized from the Glucks’ description of a typical geisha party: drinking games, shamisen playing, singing, and flirtation. However, the sense that true artistry was on display seemed secondary to simply having a good time.

The next book I read was Snow Country, by 1968 Nobel laureate, Yasunari Kawabata. The novel tells the story of an affair between a dance critic and a geisha who works in a hot spring resort town in the mountains of Niigata. Although Kawabata’s elliptical style resists definitive readings, it appeared that the geisha working in this town did more for money than simply facilitate parties. At this point I asked a Japanese friend just what the job description of a geisha actually entailed, but she confessed to knowing less about them than I did.

Around this time, I happened to hear a National Public Radio interview with Arthur Golden about his bestselling book, Memoirs of a Geisha. In the interview, Golden stressed that the Western conception of geisha was misguided. Like the Glucks, he stated that their primary role was indeed as “arts ladies.” While it was common for a geisha to become the mistress of a wealthy patron, any other type of financial arrangement was left to women of a different name working in the red light districts.

I accepted Golden’s definition wholly, especially after reading elsewhere that the trained women working in such reputable places as Gion and Pontocho in Kyoto were the only ones worthy of the name geisha. As for those women of looser morals working at the hot spring resorts, they were geisha in misappropriated name only. Convinced of their respectability, and intrigued by their arts, I decided that somehow I would have to see a geisha in performance. That would mean a trip to Kyoto.

Kyoto roughly translates as "capital of capitals," and for almost 1000 years it was Japan's, until Tokyo (literally “East Capital”) attained the status officially in 1868. However, Kyoto remains the unofficial cultural capital, and its beauty is renowned throughout the country. Its treasures are so rich that an American historian, Langdon Warner, is often credited with persuading the military to spare it from bombing during World War II.

I spent my first Christmas in Japan touring Kyoto, the birthplace of geisha. On an EFL teacher’s salary, I could hardly afford even a single geisha to entertain a friend and me at dinner, but my trusty Gluck guidebook suggested a couple likely places where we could see them walking to their next appointments. As the narrow road along the Kamo River known as Pontocho was atmospheric and convenient, we made our way there. I thought I caught a glimpse of their trademark coiffed hair on two occasions, but since neither of my friends noticed anything, I accepted their verdict that I was hallucinating. We must have walked up and down that street six times before retreating to a nearby pub in defeat. I ended up leaving Kyoto disappointed, but hoping for a chance to return.

I did return to Kyoto eleven months later in a different company of friends. Perhaps they brought me luck. It was on the very first day while walking on the Path of Philosophy from Ginkakuji (The Silver Pavilion) to Nanzenji Temple that we saw four women dressed as maiko (apprentice geisha) walking toward us. We started taking pictures as they approached and passed, revealing the fabric of their elaborate obi (belts) hanging down to their calves, which is characteristic of the maiko kimono style.

In spite of my excitement at seeing maiko in their natural environs, there was something about their comportment that made me suspect that they were “maiko for a day”--Japanese tourists who had paid approximately $120 each to be dressed and made up as maiko. As we took pictures they seemed nervous and surprised. Where was the aloofness of the glamorous maiko weary of yet another group of Western tourists-as-paparazzi? What about a coquettish professional willing to send a coy look our way for the good of Kyoto tourism and a few spellbound tourists?

Later in the day, as we made our way to Kiyomizu Temple, we saw a dozen more "maiko" pouring out of a side street, apparently confirming my suspicion that we hadn't seen authentic ones earlier. Indeed, we had already seen more maiko that day than there were probably working in all of Kyoto. Not that I was complaining, the presence of these Office Ladies in disguise evoked a period of Kyoto’s history many seek on its streets. Had my only encounter been with these replicas, I would have still left content.

Having seen these maiko-for-a-day, I had no plans to drag my friends up and down Pontocho in a potentially futile repeat of the previous year’s effort at geisha spotting. However, it had been a long day and the two women I was travelling with wanted a pint. Since they expressed their wish to me as we happened to be passing the corner of Pontocho, we turned because it also happened to be the quickest way to the one Kyoto pub I knew. So with our minds firmly focused on beer and nothing more, it happened.

A door to my left slid open. A woman stepped out right in front of me. She had an elaborate coiffed hairstyle, a perfectly painted face of white, and she was wrapped in a luxurious nightshade kimono. She brushed by me as she hurried off to her next engagement. I turned for a better look, but she was already well past us, quickly weaving her way through the crowd with the help of someone who appeared to be clearing a path. Her oversized obi with gold accents suggested that she could be only one thing--a maiko.

Throughout history, it was only the wealthy and the famous who could afford the entertainment of Kyoto geisha and little has changed today. However, thrice a year--twice in spring and once in autumn--the geisha and maiko from the leading geisha districts of Gion and Pontocho perform an hour long dance program in small theatres. The ticket prices are affordable--well within reach for any tourist short of the minimalist backpacker. Surprisingly, we were able to buy our tickets for the 41st Gion Odori on the day of the performance.

An hour before the show began, a younger geisha in an elegant black kimono stood outside the theatre. She smiled and bantered with the elderly Japanese who took turns having their picture taken with her. All the while she remained composed and gracious. Apparently the public relations benefits of this event make it well worthwhile for the geisha to perform below cost in front of the general public.

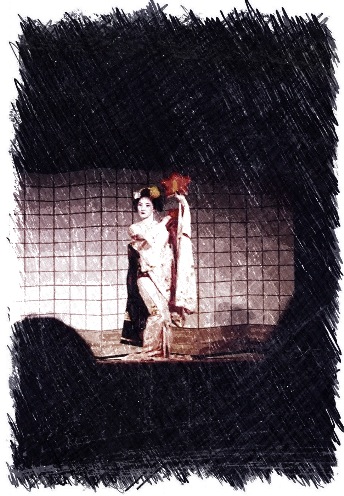

Before the dance, we entered a side room where two maiko were preparing matcha (the bitter green tea used during tea ceremony). The one on the right, Tomisuzu, wore a black kimono with a light coloured obi. The maiko who sat next to her wore a peach coloured kimono with a black obi. Unfortunately, I never learned her name. Both of them wore the appropriate seasonal flower--a yellow chrysanthemum--in their hair. Tomisuzu prepared the matcha using ornate blue earthenware decorated with gold leaf while her companion served a bowl of the frothy tea to a fortunate visitor seated in the front row. The rest of us were served by elderly assistants who made up for what they lacked in grace and elegance with hustle and kindness, making sure that a friend indifferent to matcha and Japanese sweets received a souvenir plate anyway.

The first available seats for us were in the back of the makeshift tea room, so I slipped up to take a better picture. When I raised the camera, the unidentified maiko closest to me seemed to look over as if posing for the photograph. Before the picture could be taken, someone stepped in front of me. I lowered the camera and she looked away. When I raised it again she looked back, confirming that I wasn't imagining her posing for me. After snapping the photo I thanked her for the courtesy with a small bow, unsure if she would even acknowledge me. She did--with a flirtatious smile quickly concealed by a full bow of the head that clouded my brain and had me stumbling back to my seat.

After finishing our tea, we settled into our seats in the theatre, eagerly anticipating the performance. The high pitched twang of the shamisen drew our attention to the dour faced women in simple black kimonos kneeling on the side stage. Thus it was an easy choice to focus on the main stage when three maiko (Tsunesono, Akie, and Hinano) dressed in colourful kimonos of red, blue, and pink began the opening dance, carrying seasonally appropriate red-leaved tambourines in each hand. Following this, the geisha took turns in groups of two or three acting out different stories of romance and daily life.

One comical dance depicted the story of a geisha with a baby seeking to meet her lover in a public park. As long as the geisha held the baby, it was quiet. Every time she attempted to slip off for a brief moment alone with her lover, the wailing started. This dance was performed by the two most senior geisha, both of whom were past middle-age. It was refreshing to discover that the geisha does not necessarily lose her status once the overrated beauty of youth passes.

As the final dance of the afternoon commenced, the bittersweet pleasure of having fulfilled one of my main tourist objectives in Japan overtook me. Although my friends had teased me about my fascination with geisha, I knew that now I had seen them perform, my innocent enthusiasm would fade away. Their spell was lifting, even as I watched the entire group of geisha and maiko dance the grand finale. But they had one more charm concealed in their sleeves, namely a small bundled cloth, which each of them flung out to the audience near the end of the dance. I was too surprised to react, but I didn't have to jostle with my fellow audience members. One of the bundles arced above the seats. I looked up to see it suspended in air directly above me, then it dropped into my lap. My heart pounded violently. How could they have this effect upon me? As I recovered my senses I realized that it had come from the direction of Hinano, a maiko with a haughty demeanour who had appealed to me greatly. In fact, she seemed to be dressed identically to the maiko I had photographed during tea. When I unrolled the cloth, the flowered kanji written on it matched her name.

I was enchanted, once again.

ちりて後

おもかげにたつ

ぼたん哉

chirite nochi

omokage ni tatsu

botan kana

After they've fallen,

their image remains in the mind--

those peonies

--Yosa Buson (1716-1783)

(as translated by Steven D. Carter)

For tourist information about geisha, please see my blog for a set of links.

Further Reading

Geisha: The Life, the Voices, the Art by Jodi Cobb (photographs and text)

Geisha by Liza Dalby (About the author’s experiences as an anthropology student who lived and worked as a geisha for a year in Pontocho.)

Japan Inside Out by Garet, Jay, & Sumi Gluck

Memoirs of a Geisha by Arthur Golden

Snow Country and The Old Capital by Yasunari Kawabata

Botchan by Nastume Soseki

Home